Why It took Patte O'Connor 14 years to Reveal She Was Jane Doe No. 6 in Andrea Constand's 2005 civil lawsuit against Bill Cosby – And Why She Doesn't Regret It

O'Connor spoke at a human trafficking conference at the University of Toledo on September 21st and hopes to embark on a speaking career

When Patte O’Connor , who was Jane Doe No. 6 in Andrea Constand’s 2005 civil lawsuit against comedian Bill Cosby - agreed to reveal her identity for the first time in my 2019 book CHASING COSBY, she had no idea what to expect.

Empowered by the #MeToo movement, which had burst onto the scene when I first contacted her in the fall of 2017, she wasn’t thinking that far ahead. She just knew she was finally ready to share her story publicly.

I’d long been intrigued by the Jane Does, back from when I first started covering the Cosby case for the Philadelphia Daily News in January 2005. Back then their identities were fiercely protected by Constand’s attorneys Dolores Troiani and Bebe Kivitz, who vigorously fought Cosby’s attorneys’ attempts to make them public. I understood. Not only had Constand herself been viciously attacked in the media with false information fed to them by Cosby’s people but Tamara Green, a California attorney who said Cosby had drugged and sexually assaulted her around 1970 and had only come forward with her own story in January 2005 to help convince then-Montgomery County DA Bruce Castor Constand was telling the truth, had been put through the wringer as well. Every mistake Green had ever made was leaked to the media by Cosby’s team (I know because I got one of the emails from them about her). In fact it got so bad she finally started revealing things about herself they hadn’t yet dug up.

After Castor announced he wasn’t going to charge Cosby criminally for Constand’s assault in February 2005, in a bizarre press release he would claim ten years later was an immunity agreement barring Cosby from ever being prosecuted for this case, Constand was left with only one way to get some measure of justice: a civil lawsuit against him. The 12 Jane Does were listed as supporting witnesses. But who were they? What was their story? I interviewed Jane Doe No. 5 Beth Ferrier when she came to me in June 2005 and, once I went to PEOPLE magazine, we included Ferrier’s story as well as that of Barbara Bowman, Jane Doe No. 7 and other victims who agreed to have their names and photos used in a 2006 story we published.

But the other ten stayed silent - until the Cosby scandal exploded again in October 2014. The media was a much friendlier environment for them than it had been in 2005 so one by one, they began telling their stories to various media outlets. But when I began doing some research for some Cosby-related projects in the fall of 2017, I discovered four of the twelve were still anonymous. Thinking that they might finally be ready to speak, I cross-referenced Cosby’s deposition for Constand’s case, in which he was asked about each of the Jane Does both by their numbers and their actual names, and dug through court documents until I found an old filing that listed them by numbers and the towns they lived in back in 2005.

Even with that information tracking them down wasn’t easy. In fact, I was told by one of my sources that one of the detectives on the case said O’Connor, Jane Doe No. 6, was dead. Given how poorly this case had been investigated in the past I didn’t quite believe this so I found an address for a woman with that name in Ohio and wrote her a letter asking if she’d speak with me. By then the #metoo movement was exploding, which made my quest just a little bit easier I think.

Within a few days I got a call from O’Connor. (I also wrote to and heard back from the other three Jane Does, two of whom agreed to be interviewed and allowed their names to be used in my book.) Not only was O’Connor alive and well, she was ready to tell the world what she said Cosby had done to her back in 1984 when she was an assistant director of student activities at Clemson University in Clemson, S.C.

“I’ve had a lot of time to process this,” she told me of her decision at the time. “I’ve heard the other women’s stories. I admire their courage and their bravery and putting themselves out there for people’s opinions. I admire them. I always wanted to be part of that bravery. I always wanted to stand up for women and support my sisters and now that my dad is dead, my mother has dementia and I’m older and I’m wiser and I’m more mature, it’s necessary for myself to do this. It’s perhaps part of my journey in life to do this. Maybe somewhere down the road I can help other women at any age they are stand up for themselves with sexual predators.”

Here’s an excerpt from CHASING COSBY about O’Connor:

Patte O’Connor, Jane Doe No. 6, said had been at her job as student activities director at Clemson University less than two months in October 1984 when she got a very important assignment. Comedian Bill Cosby was flying into town on his private jet and she was to pick him up at the airport at 2 p.m. He was scheduled to perform at 8 or 9 p.m. that evening during a weekend of Homecoming festivities.

“It was cool,” O’Connor, now 59 and a full-time caregiver for her mother in Toledo, Ohio. “I was waiting with the police escort. He was wearing the same red Adidas top that he was dressed in in the opening credit of The Cosby Show. I’ll never forget it. He said, ‘I’m hungry! Let’s go back to the hotel room. What’s the best place to get some burgers?’”

They got some burgers and cokes from a local burger place and brought them to his hotel room. A gift basket with a bottle of wine so that was in his room as well.

“He asked me if I wanted something to eat and I didn’t, so he was eating and we just kinda settled into talking.”

There were two twin beds in the room and a table between the twin beds, and at one point he said, ‘This bed is my bed and this bed is your bed.’ And I thought, ‘That’s bizarre. Why would you say that?’ I remember thinking how odd it was. But, of course, I was like, ‘What am I going to say?’ “So, they just kept talking.

“He was very smart, very intellectual,” she said. “We were talking about philosophy and the merits of education. It was a nice, deep conversation. He was asking me about my family, and I said, ‘My cousin in Toledo is getting married.’ He said, ‘Really? Let’s call!’ I thought, ‘How fun is that?’ ’’

By this time, the gift basket was open, and Cosby asked her if she wanted some red wine. “I said, ‘OK,’ so he gave me a glass and I never noticed that he didn’t drink; that he kept filling my glass, but I got pretty relaxed and drunk quite quickly because I had been up since 4 or 5 am. I don’t think I ate breakfast and I didn’t each lunch.”

They tried to call her cousin at her wedding, but they couldn’t reach her. They finally tracked down a phone number for the wedding reception hall, and soon Cosby was chatting amiable with her very surprised parents. “It was hilarious,” she said.

At some point, Cosby began serving her coffee and Kahlua as well. “I don’t know where the coffee came from,” she said. “He just kept making me these coffee drinks with Kahlua in them.” Then he said, ‘Are you tired? I’m exhausted. Do you want to take a nap?’ So, he points to his bed. He says, ‘Let’s take a nap.’ We’d been together for hours, so I felt comfortable with him. He was like an old buddy.”

They laid down together and he said, ‘Do you like tummy rubs or back rubs?’” she told me.

“‘I’m like, ‘Well, that’s an odd question… um, back rubs.’ ” He gave her one without taking her shirt off, then told her it was his turn and he wanted a tummy rub.

“So, he lifted up his shirt right away, brought my face close and kissed me on the lips,” she said. “That startled me. I said, ‘No. No.’ “

That’s the last thing she remembers. She woke a few hours later to the phone ringing in the room. The shower was running, so she picked it up. It was her boss.

“My boss was screaming, ‘What is going on? Where are you?’ ” she said. “I was so out of it t. We were running late.”

The next thing she remembered—it seemed like within minutes, but she wasn’t sure how much time had lapsed—there was a banging on the hotel room’s door. “It was my boss. He was pissed.” They were late for the performance.

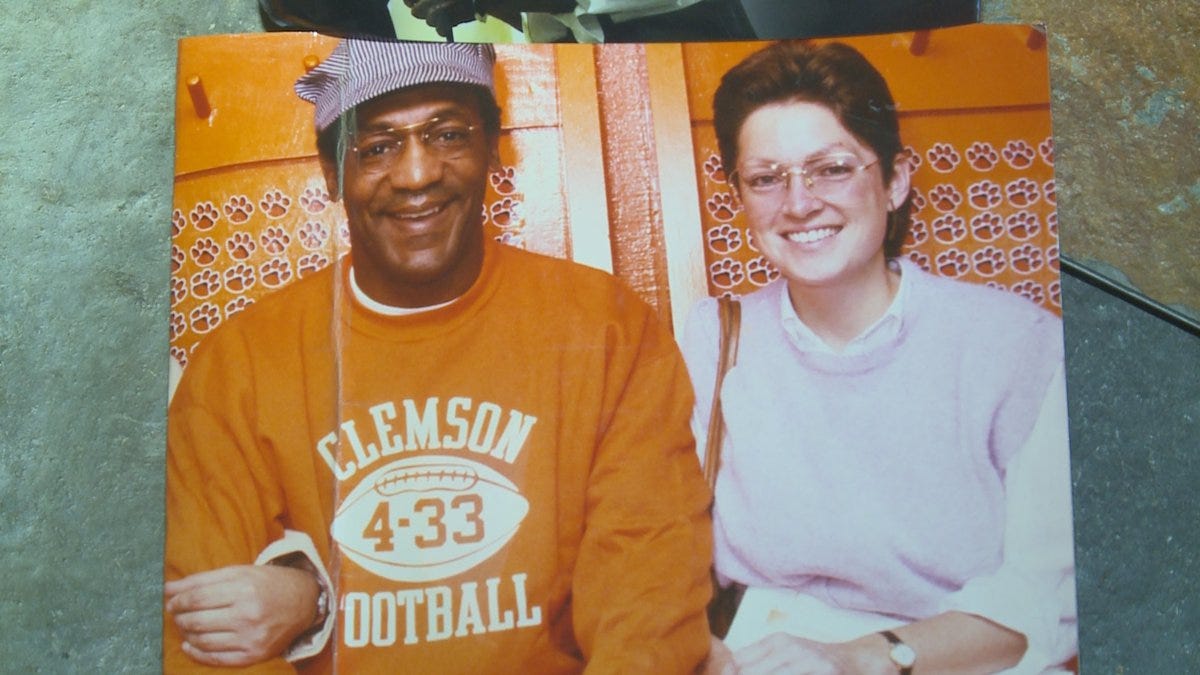

She only remembers pieces of the rest of the night: riding in the back of the police escort car, seated in between her boss and Cosby, squeezing her boss’ hand because she couldn’t speak; walking down a huge, long corridor to get to the locker room, where they’d set up a photo op with the president of the university and other big wigs; getting her photo taken with Cosby and her boss; and hearing her boss screaming at Cosby.

“He was yelling, ‘What happened? Why is Patte like this? What did you do?’ ” Then she remembers Cosby walking by her on the way to the stage and mouthing, ‘I’m sorry.’ After that, it’s all blank until she woke up in the middle of her steps leading up to the second floor of her townhouse around 3 or 3:30 a.m. Her next memory is waking up in her bed, though she had no memory of getting into her bed.

In a panic, she called her boss to apologize.

“I was upset and crying, and he said, ‘Don’t’ worry.’”

For years she thought of that incident as her “funny Bill Cosby story”—until 2005, when she saw news reports about Andrea’s claims of being drugged and sexually assaulted by the entertainer. “It hit me. ‘Oh sweet Jesus, that wasn’t a funny story. That couldn’t have been just alcohol. How could I have blacked out so much?”

She also came to realize he had probably sexually assaulted her while she was unconscious. “I thought to myself, ‘There is no way on God’s green earth that he had a woman to himself with his history, passed out, and he didn’t do anything,” she said. “It took a long time for me to process that . . . I was a victim of sexual assault. I had to have been.”

She called Andrea’s attorneys and offered her assistance, though she did not want her identity revealed, so she became a Jane Doe in the civil suit.

“I did a lot of soul searching and it was very painful,” she said. “A friend of mine told me if I did allow my name to be used I’d have reporters at my door; that my whole life would change, and this is would what I would be known for. And it scared me.”

O’Connor agreed to do interviews in her local newspaper and for a local television station when my book came out. But the reaction she got wasn’t quite what she expected. Why did you wait? You’re a liar. You just want money. You just want fame. Those were some of the comments on the news stories about her; the usual vitriol spewed at sexual assault victims. I still don’t think people realize how much courage it takes to come forth with allegations against a powerful public icon like Cosby. Unlike Harvey Weinstein and Jeffrey Epstein, whom most people had never heard of before the scandalous stories about them broke, Cosby still has millions of fans; millions of followers on his social media who refuse to believe he’s anything other than what they‘ve believed him to be for so long.

“My brother had gone on one of the websites and warned me not to read the comments,” she told me recently. “But I did and I kept reading. It was hurtful. Coming out and being public about it was an experience that you can’t anticipate until you go through it so back then yes it was upsetting because you always want to be liked; you never want to read negative things about yourself.”

But she was still glad she’d spoken out.

“It didn’t negate the fact that I’m glad I did it,” she said. “Nobody could say anything that would make me regret what I did. Ever.”

While she still hoped to be a voice for other women struggling with the aftermath of sexual assault, she had to put that dream on a back burner. O’Connor was a full-time caregiver for her mother, who was dying of Alzheimer’s, which was a 24/7 job. After her mother died in June 2020, we were in the midst of the pandemic so it wasn’t until this year that she finally got an opportunity to think about what she wants to do next. She’s hoping to embark on a speaking career, and started with a speech at the human trafficking conference at the University of Toledo on September 21, (the video is above) followed by a Q and A session with Dr. Celia Williamson, executive director of the University of Toledo’s Human Trafficking and Social Justice Institute.

Afterward, a family trafficking survivor reached out to her, which was even more gratifying.

“She said my speech helped her understand more about her own trauma,” O’Connor said. “I was surprised as I had no idea how what happened to me could extend to another person who experienced a form of sexual trauma. It was similar to what happened to me when I found out Andrea Constand went to the police about Cosby in 2005. It was another woman using her voice and opening up and telling her story. You never know the healing power of our own words can help someone on their own journey to find their inner truth.”

The eexperience was all that she hoped it would be - and more.

“It was another ‘coming full circle’ moment,” O’Connor told me. “I thought when I came out in the book and then in the local media that was the one and only full circle experience. This felt like I was sharing with my tribe. The purpose and intention was to help and serve others who have experienced sexual trauma. It was over-the-top killer rewarding and I hope that speech was the beginning of many more to come.“