Where is Cherrie Mahan?

Forty years after the eight-year-old little girl vanished less than 100 yards from her Butler County, Pa. home, her mother still desperately hopes for answers

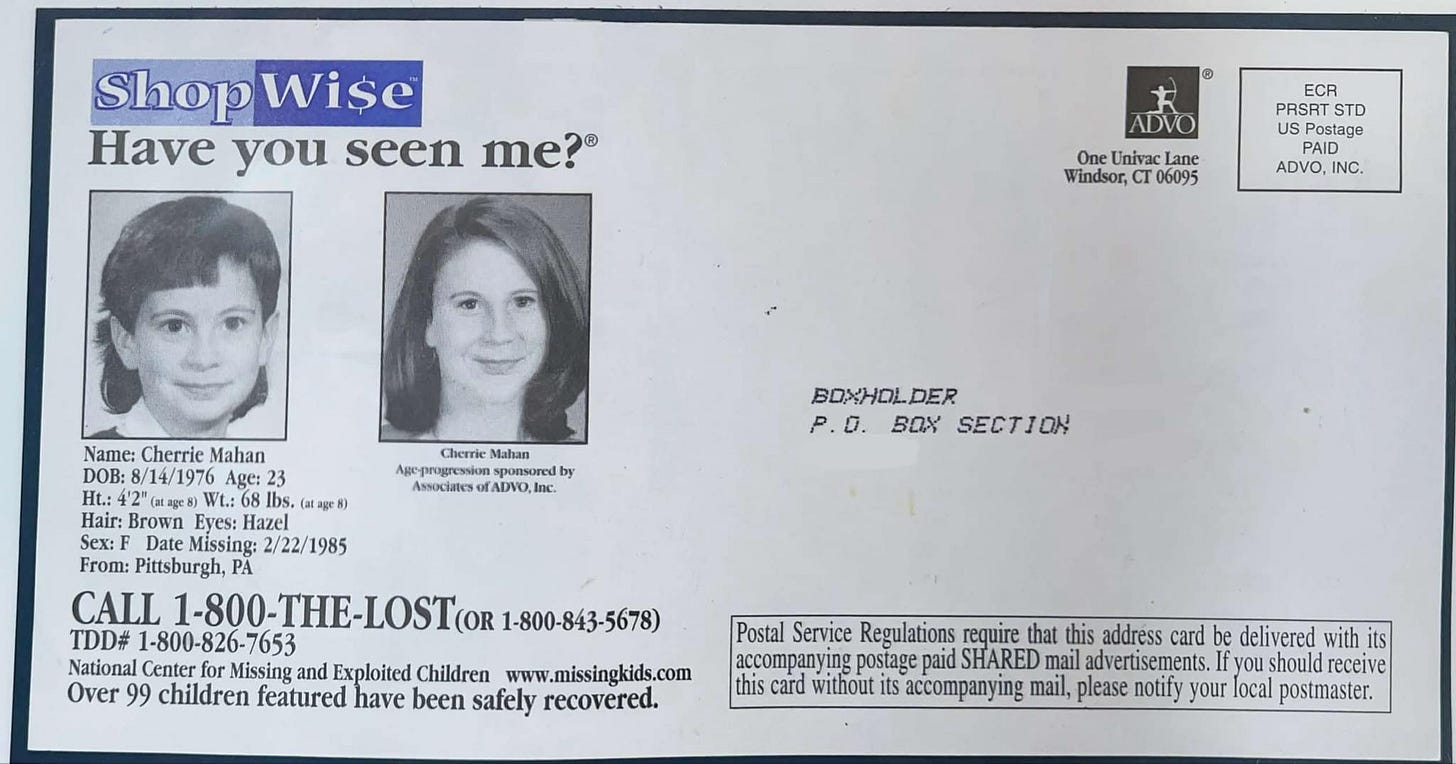

In many ways, Cherrie Mahan was a typical eight-year-old little girl. At four feet, two inches tall and 68 pounds with brown hair, cut short in the front and long in the back, a cowlick that refused to be tamed, hazel eyes, and an impish grin, she loved Care Bears, reading, and spending time with her three best friends, Tiffany, Jenn, and Kelly. “She cared about everybody,” her mother, Janice McKinney, now 64 and retired from her job as head of housekeeping at a local nursing home, told CHASING JUSTICE. “She wanted to be a schoolteacher. She was my mother in a little person. She loved God. She just was a wonderful child.”

But in the weeks and months before she vanished, the vivacious, friendly little girl was scared. She told her mother that someone was looking in her bedroom window at night. Though they’d recently moved into their new home and her mother had given her a big bedroom at the front of the trailer, Cherrie begged her to move her into the smaller bedroom in the middle of their home. Janice finally relented, and even bought thermal curtains for her new room, hoping their thickness would help Cherrie feel safe.

Even that wasn’t enough. Half the time Cherrie slept curled up on the floor next to her bed, with no covers, her Cabbage Patch doll, Care Bear, and Popple doll still neatly lined up on the bed itself, she said. “I believed her,” Janice said. “She was truly afraid. At the same time, she didn’t know what, if anything, to do about it. They had just moved to their home in Cabot in Butler County, Pa., and were now living in the Boonies, as she liked to call it, with their only visible neighbor living in a trailer behind theirs, so who could possibly be looking in Cherrie’s bedroom window?

A few months later, on February 22, 1985, at 4:10 p.m., Cherrie stepped off her school bus with three other children less than 100 yards away from her Butler County, Pa. home, walked around the bend in the road, which led to her driveway – and vanished into thin air. Witnesses reported seeing a 1976 blue Dodge van with a decal of a mountain and a skier on the side following the bus. Reports later emerged of a small blue car parked in a neighbor’s driveway for no apparent reason that seemed suspicious, but despite thousands of tips, countless searches, extensive publicity from being the first child featured in the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children’s “Have You Seen Me” postcard campaign that went to millions of households across the country, and more than a few red herrings, the van and car have yet to be tied to an owner and Cherrie’s fate remains a mystery.

Cpl. Max DeLuca of the Pennsylvania State Police, which has been the lead investigative agency on the case for the last four decades, said it is still an open investigation. “There is no one suspect but multiple persons of interest,” said DeLuca, who would only answer questions via email and through a spokesperson.

On Saturday, the 40th anniversary of her disappearance, Janice will do what she’s done every year since her daughter vanished – hold a vigil at the spot where she was last seen. Later that day she will host a get-together, along with the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children, at the Saxonburg, Pa. VFW to both honor her daughter and thank everyone who’s been there for her over the years. The event will be open to the public and free fingerprinting for children will be offered. There will also be a raffle, the proceeds of which will go toward hiring a private investigator to help with the investigation, said family friend Bailey Gizienski, who started a new Facebook page, Find Cherrie Mahan, with her wife and sisters, on January 19th hoping to generate new leads in the case. (Another Facebook page, Memories of Cherrie Mahan, is run by someone with no connection to Janice, Gizienski said.) As always, Janice hopes the new round of publicity and the Facebook page may jog someone’s memory and prompt them to come forward with what they know because if there is one thing she is certain about it’s this: Somebody somewhere knows what happened to her daughter.

“I’m just hoping that somebody finally takes the initiative to at least tell me what happened,” Janice said. “If I could have a bag of bones, I at least would have some comfort. But the not knowing is what sucks the life out of you.”

Janice was just 16 years old, still a child herself, when she gave birth to Cherrie at Butler County Hospital in Butler, a small city about 35 miles north of Pittsburgh in western Pennsylvania, on August 14, 1976. Janice had four siblings and her father worked long hours at the gas station they owned, which left McKinney, a “rebellious 15-year-old as she described herself, plenty of time to go places she shouldn’t have, certainly not at her age, and get into situations she was far too young to understand, let alone handle. Which is how she met Cherrie’s biological father, who was much older than she was and took advantage of the situation.

“He was a motorcyclist and I was an easy target because I wanted to be liked,” she said."So when you get those feelings you’ll do anything to anybody, for anybody… I just was an easy target. When she found out she was pregnant, at first she was scared, but she never thought twice about not having Cherrie. “At that time I had three other friends that were going to have babies too,” she said, “so it was like our little clique but out of all of us I’m the only one who stayed in school. I’m the only one who graduated. I had Cherrie in August so I made it through school without many people knowing.”

Including her parents. She hid the pregnancy from them as long as she could, but eventually it was all too obvious she was pregnant. They offered to help her raise Cherrie but urged her to finish high school, which she readily agreed to do. Cherrie’s biological father, meanwhile, refused to believe he was her father. “He denied everything from day one and … that was fine,” she said. “I never bothered with him. Because he didn’t think he was Cherrie’s father. And it was my word against his. And that’s the way it was.”

Her parents doted on Cherrie, especially her father, who had missed so much of his own children’s childhood working long hours at the gas station they owned. Janice not only finished high school, graduating in 1978 but went on to community college for a couple of years. She wanted to go to cooking school but after her father died in 1981 it just wasn’t possible. She met Leroy McKinney, a Vietnam veteran, not long afterward and married him the following year. Cherrie was a flower girl.

Janice began working as a housekeeper at St. Barnabas, eventually working her way up to become the head of housekeeping. She, Leroy, and Cherrie moved to their new home, a trailer that sat on top of a hill in Cabot, in the summer of 1984. Cherrie quickly made friends at her new school. Janice had to leave for work at 5 a.m. so she’d wake Cherrie, grab a backpack with her clothes to wear to school that day, and take her to a neighbor’s house where she’d sleep until it was time to catch the bus. At first, she let Cherrie pick out her clothes, she said.

“Then she came home from one school one day with her penny loafers on, knee-high pantyhose, a plaid skirt, and a striped blouse and I was like, ‘Oh dear God. They probably think I’m some crazy woman,’” she said. “And Cherrie loved looking like that. It didn’t bother her a bit. From that point on I always made sure what she put in her backpack to wear to school. She loved her Jordache jeans and her penny loafers.”

Friday, February 22, 1985, started off like any other school day. Janice got Cherrie up and dropped her off at the neighbor’s house with promises of buying her a new Care Bear that day to replace the one their dog had eaten and a knapsack filled with her clothes for the day – a grey coat, blue leg warmers, Cabbage Patch ear muffs, a white leotard, and tan ankle-high boots. She was carrying her blue book bag, which likely contained the school pictures her third-grade teacher at Winfield Elementary School had passed out that day. Cherrie was a little chatterbox, her teacher would later tell the [Pittsburgh] Tribune-Review, so that day she moved Cherrie’s desk to the front of the classroom hoping it would help keep her quiet. It was a decision she would later regret, Cherrie’s empty seat a constant reminder that the little girl was gone.

Because Janice worked such early hours, she was off by the time Cherrie’s bus dropped her off at 4:10 p.m. and normally walked down their long driveway to meet her at the bus stop. That day she’d gone shopping for a new Care Bear for Cherrie since their dog had chewed off the face of her old one and was looking forward to seeing her daughter’s reaction to it. Cherrie was excited about having a sleepover with her friend that night and had already told what she wanted for dinner that night – tuna fish with melted Velveeta cheese on an English muffin, something Janice’s mother used to make, a meal she still can’t bear to eat.

But it was an unusually balmy February day so Janice decided to let Cherrie walk from the bus stop herself, a decision she would come to regret. “Every single day since we moved there I was down there to pick her up,” she said. “I felt guilty and still do. Because I should have been there and I wasn’t.”

She and Leroy heard the school bus but when ten minutes had gone by and Cherrie still wasn’t home, Leroy went down to check on her and said she was nowhere to be found, Janice said. “I said, ‘We’ve got to go. Maybe she forgot to get off the bus,’” she said. They jumped in their truck and raced to catch up the bus. “The bus driver said Cherrie had gotten off the bus at her normal stop and the kids that got off the bus with her had already gone up their driveway,” she said. Those children would later tell police they saw the blue van with the mountain scene and the skier following behind the bus, “but when we got to that bus there was no van behind it,” she said.

They went home and Janice called her mother in a blind panic. “I said, ‘Cherrie didn’t come home. Can you come over here?’ and she said, ‘Call the police,’” Janice said. “And probably within an hour or two, they were there. I was beside myself because Cherrie was all I had.”

The police conducted a 5-mile search using bloodhounds and walked the woods around their home, to no avail. The bloodhounds could not pick up a trail beyond where the children had said the blue van was and found nothing else to go on. Cherrie was gone. The only leads were the blue van that had been following Cherrie’s bus and, later, a blue car that was spotted in a nearby driveway. Janice isn’t sure anymore whether the blue van was a viable lead or a red herring.

“When they started talking to the kids-yes I think there was a van behind the bus but I also believe that they kind of led those kids to say what they thought they saw,” she said. “You know, like a police officer could – and I wasn't there and I don't know how they talked to them – 'Oh, there was a skier. Did the skier have a blue hat? Yeah, he had a blue hat. So do I believe it? I don't know, but I also believe that there was another car parked in a driveway that probably had something more to do with it than we believed at the time. It was in another driveway and Cherrie had to walk past this driveway to get to ours. That was something that was not talked about right away because the kids mentioned the van and that’s all they talked about.”

Janice also told the police about Cherrie’s fears that someone had been watching her in her bedroom, but police say there is no way to know if it was connected to her disappearance until someone is arrested. Both Janice and her husband, who has since died, passed lie detector tests given by the state police to rule them out as suspects.

From the very beginning, Cherrie’s case captured the nation’s attention. In May 1985, the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children [NCMEC] chose to feature Cherrie as the first missing child to be featured in its new Have You Seen Me? postcard campaign. “She disappeared just months before the launch and investigators were actively pursuing leads,” said Angeline Hartmann, Director of Communications for the NCMEC, of why Cherrie’s case was chosen for the first postcard. “Forty years later, we believe the answers about what happened to Cherrie are still out there. We encourage anyone to come forward if you have information. It’s never too late.”

As the months passed with no answers, drowning in grief and guilt, Janice fell into a deep pit of addiction, looking for something, anything to take away the unbearable pain. By the time she shook herself out of it nearly a year later, she’d lost everything. Her new home, once filled with so much hope and love, was foreclosed on by the bank because she wasn’t able to make her mortgage payments. And she was flat broke.

“I hit rock bottom,” she said, “and I said, ‘I’m never doing another drug.’ And I haven’t.”

She slowly rebuilt her life, but the uncertainty about her daughter’s fate wrapped up in the aching, unbearable loss of a child, has taken an emotional toll on her over the years. She planted a Japanese cherry tree in her honor near an angel statue at St. Barnabas “People don’t understand the heartbreak,” she said through tears. “I look at somebody that could be Cherrie’s age and I think, ‘Oh my God. What have I missed?’ I didn’t get to see her graduate. I didn’t get to see her have kids. She’d be 49 years old today and that’s horrible. Like I said, just the not knowing is what can kill you.”

Even worse is the false hope that comes with every new lead. It’s always, always followed by a fresh round of despair. Women have even come forward over the years claiming to be Cherrie all grown up, one as recently as earlier this year. Fortunately, since Cherrie had her fingerprints taken as part of a school program, police can rule them out fairly quickly instead of waiting for DNA test results.

“You get somebody that truly believes they’re Cherrie and no matter what you say to them they truly believe it,” she said. “It breaks your heart every time something like that happens. Trooper DeLuca is my first line of defense.”

One woman from Rochester, N.Y. whose name is actually Cherrie Mahan, called Janice directly, convinced she was her long-lost daughter.“ I spent a weekend with her hoping it was Cherrie and it wasn’t,” she said. “Of course I still talk to her.”

Even after all this time, there isn’t a day that goes by that she doesn’t think of her lost daughter.

“Every morning before I get out of bed I pray that the good lord tells me something because I don’t know what else to do anymore,” she said. “This is the hardest. I mean over three-quarters of my life I’ve spent looking for her.”

If you have any information about Cherrie Mahan’s disappearance call the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children at 1-800-THE-LOST or the Pennsylvania State Police Missing Persons Unit at 724-284-8100.